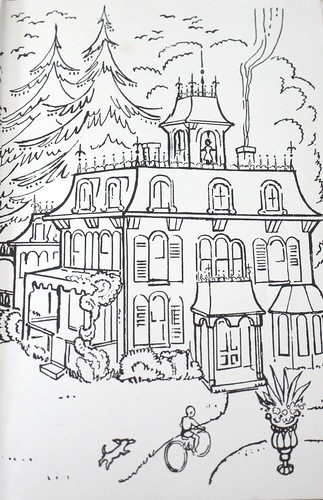

The Four-Story Mistake, the sequel to The Saturdays, picks up some months after that book left off: it’s October, and the Melendy family is moving out of their Manhattan brownstone to a house in the country. As in The Saturdays, the characters and the story are charming, and Enright is emotionally astute: I loved this, from moving day: Randy is looking around at the empty room she used to share with Mona, talking to herself “crossly because she was sad and she preferred sounding cross to sounding sorrowful, even though there was no one in the room except herself” (3). None of the kids, other than Oliver, who’s the youngest and the most forward-looking, are thrilled to be moving, but once they arrive in the country they start to see their new home’s appeal. The family moves into The Four-Story Mistake: a house built in 1871 that was meant to have four stories, but only has three plus a cupola. Each kid has his or her own bedroom (which is new and exciting), and they have the attic to themselves for a playroom (just like they did in their old house), and the new house has the bonus of the surrounding land: a lawn to play on and woods for exploring and a brook to splash in.

As in the last book, there’s humor as well as charm: I loved the episode in which Rush sneaks out early one morning to explore, has breakfast with Willy Sloper (who does odd jobs for the family and lives in a room off the stable) and then has to have a second breakfast cooked by Cuffy, the housekeeper: he feels (and looks) ill afterward, and offers this by way of explanation to Mona:

Rush paused wearily, like an actor playing Hamlet. “Mona,” he said, “it might interest you to know that I’m carrying a heavy burden. For breakfast today I was forced by circumstance to consume four eggs: two fried, two boiled. Also nine pieces of bacon. Nine. Also one bowl of oatmeal, man-size. Also one piece of toast as big as a barn door, with marmalade on it. Also one glass of milk, and two large cups of black coffee. Now do you understand?” (29)

And there’s lots of satisfying description, too, like this passage, when Randy and Rush go wading in the brook in the springtime:

The water embraced their rubber boots and inside the boots their toes felt cold but protected. Rush and Randy bent down looking for caddis houses. They invaded a wet, mysterious world. The water was dark and clear, like root beer, and on the bottom they saw shifting sand and pebbles, water-sodden twigs, and glittering flakes of mica. (167)

I also like how in this book, as in the last one, childhood independence is such a key part of the stories: the kids are cared for by their father and Cuffy, and they have school and homework and chores, but the focus is on the things they discover for themselves or choose for themselves: they decide to put on a Christmas music/dance/theatre extravaganza, or to build a tree house, or to explore indoors, or to go skating on the frozen brook, and those stories are the ones Enright tells us.

Leave a Reply to Danya Cancel reply